Tech Landscapes as Art and Research

Submitted by our 2018 ARC Fellow Team:

Marcus Owens (Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning) and Louise Mozingo (Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning)

Until recently, Silicon Valley was known as a diffuse agglomeration of unprepossessing office parks stretched out along the freeways extending some 100 miles down the peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose. This amorphous place began to take a decisive form following WWII, when land rich but cash poor Stanford University sought new means of generating much needed income—they could not sell any of the 6000 acres they owned. Establishing the 1951 Stanford Industrial Park belied its name as the university expected “smokeless” industries to tenant what was essentially an office park with local Varian Associates and Hewlett-Packard as early tenants. In contrast to the corporate campus or corporate estate that are owned and operated by the corporation, the office park functions as a speculative development within which companies lease land. This arrangement is especially suited to research and development operations, where ownership is traded for flexibility and access to the local innovation ecosystem that incubated the “Fairchildren,” famously spun off from Shockley semi-conductor in 1957. A prominent example of this corporate calculus is the Xerox PARC opened in 1970 on the Stanford Industrial Park land. 3,000 miles from corporate headquarters in Rochester, NY, cubicles gave way to beanbag chairs and a library stocked from the Whole Earth Truck Store, where researchers began to re-conceive of computers as user-friendly tools for personal communication and creative expression. As landscape architects, one goal for our research is to understand how these techno-utopian visions and narratives of “counterculture to cyber-culture” may relate to ideals about urbanism and the environment taking form in the Bay Area during this time.

Until recently, Silicon Valley was known as a diffuse agglomeration of unprepossessing office parks stretched out along the freeways extending some 100 miles down the peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose. This amorphous place began to take a decisive form following WWII, when land rich but cash poor Stanford University sought new means of generating much needed income—they could not sell any of the 6000 acres they owned. Establishing the 1951 Stanford Industrial Park belied its name as the university expected “smokeless” industries to tenant what was essentially an office park with local Varian Associates and Hewlett-Packard as early tenants. In contrast to the corporate campus or corporate estate that are owned and operated by the corporation, the office park functions as a speculative development within which companies lease land. This arrangement is especially suited to research and development operations, where ownership is traded for flexibility and access to the local innovation ecosystem that incubated the “Fairchildren,” famously spun off from Shockley semi-conductor in 1957. A prominent example of this corporate calculus is the Xerox PARC opened in 1970 on the Stanford Industrial Park land. 3,000 miles from corporate headquarters in Rochester, NY, cubicles gave way to beanbag chairs and a library stocked from the Whole Earth Truck Store, where researchers began to re-conceive of computers as user-friendly tools for personal communication and creative expression. As landscape architects, one goal for our research is to understand how these techno-utopian visions and narratives of “counterculture to cyber-culture” may relate to ideals about urbanism and the environment taking form in the Bay Area during this time.

Following formative decades of the 1960s and 70s, Silicon Valley’s reputation was firmly established and becoming a model exported around the world. As innovation shifted from hardware to software in the 1980s and 90s, massively successful new enterprises like Oracle and Cisco emerged with the “dot-com boom” that followed Bill Clinton’s deregulation of telecommunications industries. However, it was not until the ascendance of the “web 2.0” and platforms such as Google and Facebook, closely linked to personal devices pioneered by Apple, that Silicon Valley began to take a self-consciously manifest itself on the landscape, first in retrofits of dot-com offices from the 1990s, and more recently as signature corporate headquarters. These new forms reflect the unique tastes of their target workforce, the marketing of corporate sustainability policies, and a new concern for workplaces as a medium to project a distinct corporate image. In particular, the Googleplex forecasted this shift in the manner in which companies could employ their workplaces in competitive dominance. In 2004, Google leased the former headquarters of Silicon Graphics Incorporated (SGI), adding a playful array of Google-colored umbrellas to the courtyard, solar panels on the roofs and over the parking lots, and, notoriously, playground office accessories such as hammocks, pool tables, and slides between floors. In 2012, Facebook followed Google in retrofitting a dot-com era office park into a custom-built structure- reconfiguring the interior garden space as a fantasy landscape featuring a strolling Main Street, complete with candy store, roll up garage spaces, diners, bike shop, sushi bar, and large plaza emblazoned with the word HACK, easily read from GoogleEarth should you happen to search “Facebook Headquarters, Menlo Park.”

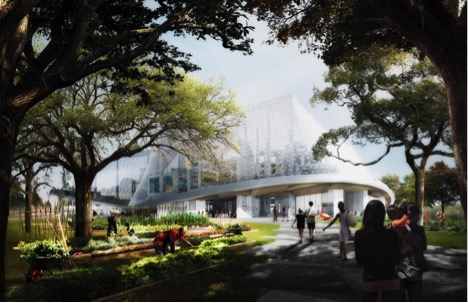

Facebook has forged ahead across the street, buying up additional adjacent office lots, demolishing existing structures, and hiring Frank Gehry to design a new headquarters. Half a million square feet, including one single open plan office of 100,000 square feet, composed of four rectangular volumes across a long site above underground parking. On top, full grown trees that shade cafés, workbenches, and picnic tables adorn an undulating grassy greenroof. Gehry’s work for Facebook reflects a broader aim for tech landscapes to convey a singular, urbane appearance with flourishes. Even long-term tenants such as Samsung and Intuit are undertaking new construction, and LandBank, a decades old Silicon Valley developer, demolished one of its 1970s Sunnyvale office parks to make way for a set of landmark office buildings. Amidst this new wave of developments, we can identify Apple’s 2009 announcement of Norman Foster designs for a new campus as a watershed moment, a suburban corporate estate conjuring the postwar titans of American industry, the sort of structure heretofore unseen in the Silicon Valley. At a price tag of five billion dollars, a severe circle of glass a quarter mile in circumference is set within a bucolic recreation of an oak-studded coastal California grassland, with parking carefully relegated underground or in separate perimeter structures. Apple was soon joined not only by Facebook in building custom flagship campuses, but also Google, who commissioned Bjarke Ingles to design Googlepex 2.0, “more of a workshop than a corporate office” as a “model of the workplace of the future.” With renderings animated by bodies in the midst of vigorous exercise rather than staring at computer screens, and structure schema of interchangeable modules set beneath sweeping geodesic-inspired lattice, using architecture achieve environmental design goals of flexibility, creativity, and innovation.

These new tech landscapes have prompted immediate comparisons to the hippie utopian design aesthetics epitomized by the Xerox PARC’s beanbag chairs, a genealogy that runs through the Whole Earth Catalog, Co-Evolution Quarterly, the Whole Earth ‘Lectric Link (WELL), to Wired Magazine and Burning Man. These forums featured clear precedents for these designs as well as broader notions of urbanism and the environment such as, Jane Jacob’s interest in urban complexity and spontaneity, Archigram’s Plug-In City, Ant Farm’s early experiments with inflatable architecture, or speculative proposals for Space Colonies presented by Ames Center Researchers at Stanford in the summer of 1970. However, some argue that this repackaged 1970s techno-utopianist attempt at integrating innovation into the architectural schema, risks becoming sclerotic, and losing the dynamism of the office park model that many have attributed to Silicon Valley’s success. Others, pointing to a “California Ideology” and the legacy of the cultural cold war, may see these architectures as new citadels of power – West Coast pentagons where smoothed edges and rhetoric of empowerment and sustainability bely ruthless algorithmic systems of social and political control. In either case, there can be no doubt that these new tech campuses are transforming the urban landscape well beyond their high-performance building skins. The early 2010s saw the issue of “google buses” – private shuttles operated by tech companies transporting employees from San Francisco’s vibrant neighborhoods to Silicon Valley’s suburban offices – take center stage in city politics as a lightning rod for the broader and more difficult problem of gentrification. Adding to this dynamic, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee negotiated a special tax exemption to keep Twitter in the city, soon joined by Uber, Square, and others, forming social media universe’s most prominent public space out of the city’s former theatre district, previously on the decline since the proliferation of home television.

To be sure, Twitter’s power-play illustrates broader urban dynamics at work across the world as cities struggle to reinvent themselves in the image of Silicon Valley in hopes of attracting the coveted “creative class,” witnessed in cases such as the transformation of Dublin’s Docklands district by Google. In what is perhaps an inevitable development of “the creative city” colliding with the “smart city,” Google affiliate Sidewalk Labs is taking on the design and development of an entire district in Toronto. In light of these developments, in addition to the Xerox PARCs bean bag chairs, it may be fruitful return to the Stanford Industrial Park’s unassuming modern architecture within this genealogy of tech landscapes. In particular, the rise of Berlin as Elektropolis, the center of the second-industrial industrial revolution where electrical and chemical technologies ruptured the time-space of everyday life in ways that set the precedent for Silicon Valley’s ethos. Following the shock of the first world war, Weimar’s modernists deployed emergent technologies to address the basic requirements of the population, an Existenzminimum of green space, sunlight, and running water. As cholera returns to the Bay Area’s encampments and shanties, collective and public housing projects such as the Siemensstadt help us imagine alternative future tech landscapes.

Marcus Owens is a PhD candidate in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at the Berkeley College of Environmental Design, and a designated affiliation in Science and Technology Studies with the Berkeley Center for Science, Technology, Medicine and Society.

Louise Mozingo is Professor and Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning. She is a member of the Graduate Group in Urban Design of the College of Environmental Design and Director of the American Studies program of the College of Letters and Sciences at the University of California, Berkeley. She was named a Richard and Rhoda Goldman Distinguished Professor of Undergraduate and Interdisciplinary Studies in 2017.

Note:Over the course of the spring semester, each 2018 ARC Fellows team will submit a short blog post about their project and findings. We hope you will enjoy these short readings! The Fellows Program advances interdisciplinary research in the arts at UC Berkeley by supporting self-nominated pairs of graduate students and faculty members as they pursue semester-long collaborative projects of their own design. To learn more about the program, click here.